“Main Kashmir hua, is liye bhi katl bar bar hua” (मैं कश्मीर हुआ , इस लिए भी क़त्ल बार बार हुआ ) – I am but Kashmir, and hence my truth was slaughtered time and again

These words capture something profound about the nature of truth in a land where history itself has been weaponised. In Kashmir, even a loaf of Bread can start a war. In 1932, it wasn’t war but Pogrom that continues to burn humanity through the century.

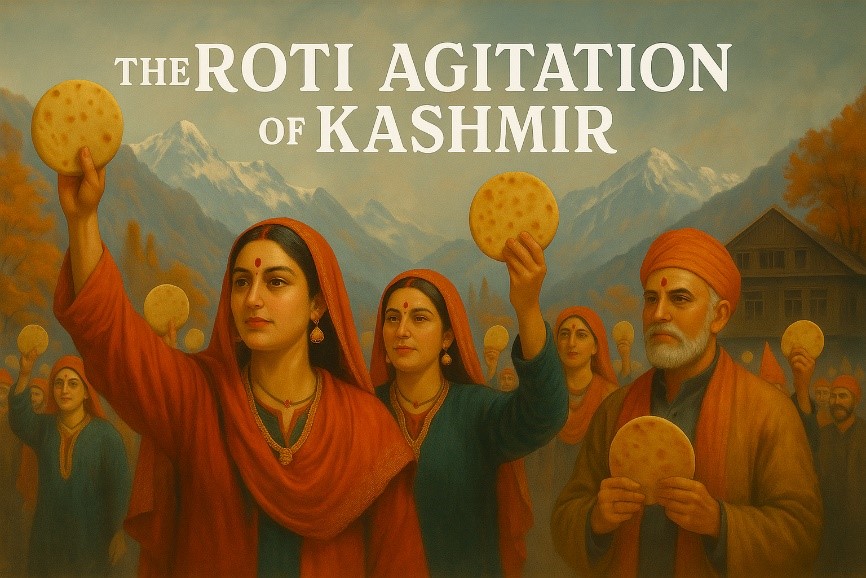

Picture this: It’s 1932, and a group of Kashmiri Pandits, scholarly Brahmins who made up barely 5% of the valley’s population, are walking through Srinagar’s streets carrying rotis. Not as food, but as symbols. These simple flatbreads have become their desperate plea: “This is our livelihood. This is all we’re asking for. the right to earn our daily bread.”

They couldn’t have known that this humble gesture would unleash a century of bloodshed, or that these same rotis would one day be remembered not as symbols of survival, but as the spark that lit Kashmir’s longest fire.

The Anatomy of a Tragedy

The year 1932 doesn’t appear in most history textbooks about Kashmir. It’s overshadowed by 1947, by 1989, by the larger dramas of Partition and insurgency. But 1932 was the year when the mathematics of Kashmir’s future were written, cruel calculations that would be paid for in blood across generations.

The Glancy Commission had just recommended job reforms that would break the Pandits’ hold on the bureaucracy. To understand what this meant, imagine being told that the one thing your community had excelled at for centuries, education, administration, the patient work of scholarship, would no longer guarantee your survival. For a minority community with no land, no business networks, no alternative source of livelihood, this wasn’t reform. This was an existential threat.

So, they took to the streets with rotis. In any other place, at any other time, this might have been seen as a peaceful, even poignant form of protest. In Kashmir, in 1932, it became the catalyst for something far darker.

When Bread Became Poison

The Muslim response was swift and devastating in its simplicity: economic boycott. But this wasn’t just any boycott, it struck at the very heart of Kashmir’s syncretic culture.

Qasais (butchers) refused to sell meat to Pandits. Milkmen stopped their deliveries. Darzis (tailors) wouldn’t stitch their clothes. Most painfully, Wazas (traditional chefs) stopped preparing the elaborate special Kashmiri exotic feasts that had been the centrepiece of Kashmiri celebration for centuries. Those were the days when Pandits were compelled to adopt these professions for survival; a piece of History that has been forgotten; perhaps erased.

Imagine the psychological impact: in a single stroke, Pandits were cut off not just from basic necessities, but from the very cultural practices that made them Kashmiri. The message was clear; you may live here, but you don’t belong here.

But the boycott was just the beginning. What followed revealed how quickly civilization’s veneer can peel away when grievance meets opportunity.

The Massacre That History Forgot

July 13, 1931. The date is remembered in Kashmir, but what’s remembered is only half the story, and perhaps not even the most important half.

The official narrative goes like this: Muslim protesters gathered outside Srinagar Central Jail during the trial of Abdul Qadeer, an anti-Dogra activist. When it was time for Zuhr prayers, the crowd began offering namaz. Dogra troops opened fire. Twenty-two worshippers died, including multiple muezzins who heroically stepped forward to replace each fallen prayer leader.

This much is true. British dispatches confirm it. But what followed, the part that history textbooks prefer to skip, was the Batte Loot pogrom.

Batte, that’s what Pandits were called, a term that honoured their devotion to scholarship and learning. But in July–August 1931, being called Batte became a death sentence.

The Pogrom That Shaped a Century

What happened next reads like a handbook on how to destroy a community’s soul:

Sacred spaces became sites of desecration. Seventeen temples were ransacked. At the Shankaracharya Temple, one of Kashmir’s most ancient sacred sites, mobs smeared beef on Shivalinga. At Sharika Devi Temple, they burned the Nilamata Purana, the foundational text of Kashmiri Hindu culture. It wasn’t just destruction; it was deliberate cultural annihilation.

Women became weapons of war. Survivor accounts describe gang rapes inside desecrated temples, with perpetrators chanting “Yeh Batte ki izzat loot lo!” (Loot the honour of these Pandits!). In Baramulla, twelve women were assaulted at Shiva temple. The message was clear: your bodies, like your gods, belong to us now.

Death became a luxury. When Pandits died, crematorium workers refused to handle their bodies. Families had to cremate their own dead, violating ancient Brahminical practices. Even in death, they were made to feel untouchable.

The British documented an 18% Pandit exodus after the pogrom. But numbers can’t capture what was really lost, the sense of home, the assumption of safety, the basic trust that allows a community to sleep peacefully at night.

The Post-Truth Empire

Here’s where the story becomes a masterclass in how truth dies in the service of power. In the decades after 1947, a different story began to take shape, one that would make the Pandits not just witnesses to oppression, but its architects.

Sheikh Abdullah, Kashmir’s rising political star, needed a narrative that would justify his vision of a Muslim-majority Kashmir. The Dogras were convenient villains, but they were gone. The Pandits, however, were still there, a visible minority that could be blamed for past injustices and future anxieties.

So, the narrative shifted. The Pandits’ educational achievements became “Brahminical privilege.” Their administrative roles became “systemic oppression.” Their very presence became a reminder of an unjust past that needed correcting.

This wasn’t just propaganda, it was something more sophisticated and more dangerous. It was the creation of a historical truth that served present political needs, regardless of actual facts.

The Irony That Kills

Perhaps the cruellest twist in this story is what happened to the laws that the Pandits themselves had championed.

In 1927, a Kashmiri Pandit courtier named Rattan Lal Kaul persuaded Maharaja Hari Singh to enact the State Subject Law; a legislation that would protect all Kashmiris, regardless of religion, from outside economic competition. This law was later enshrined in Article 370 of the Indian Constitution.

Kaul and his fellow Pandits could have crafted these laws to give themselves special protections. They had the influence, the access, the political capital to ensure Hindu-specific safeguards. Instead, they chose inclusivity. They wrote laws that protected Kashmiri identity for all Kashmiris, Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, and Buddhist.

By 1990, these same inclusive laws were being used to justify their expulsion. Islamist militants invoked “state subject” principles to declare Kashmir a “Muslim homeland,” issuing the ultimatum that would echo through history: “Raliv, Tsaliv, ya Galiv” ; Convert, Leave, or Die.

The laws meant to protect all Kashmiris became the justification for ethnically cleansing one community. The very inclusivity that the Pandits had championed became the weapon used against them.

The Global Pattern

Kashmir’s story isn’t unique, it’s a case study in how empires, both colonial and post-colonial, use identity as a tool of control.

The British perfected this technique across their empire. In South Africa, the Group Areas Act, displaced Black communities using legal mechanisms that appeared race-neutral. In India, they amplified Hindu-Muslim tensions to justify their continued presence. In Kashmir, they documented Muslim grievances in detail while minimizing Hindu suffering.

But the post-colonial state learned these lessons too well. Independent India’s treatment of Kashmir’s minorities followed the same playbook: amplify majority grievances, minimize minority suffering, use legal mechanisms to achieve demographic goals, and always maintain plausible deniability.

The pattern is depressingly familiar: a minority community achieves some measure of success through education and hard work. The majority community, facing genuine economic and political challenges, is told that the minority’s success is the cause of their suffering. Laws are passed, narratives are crafted, and eventually, the minority is removed, not through open violence (that would be barbaric), but through legal, political, and economic pressure that makes their lives unbearable.

The Education Trap

There’s a particular cruelty in how the Pandits’ dedication to education became a liability. For centuries, they had invested everything in learning: Sanskrit, Persian, Urdu, English; whatever language offered opportunity. They built libraries, preserved manuscripts, created schools.

But in the new Kashmir that emerged after 1947, this dedication to education was reframed as evidence of disloyalty. How could you be truly Kashmiri, the argument went, if you were more comfortable with books than with the soil? How could you claim to represent Kashmir if you spoke the languages of outsiders better than your neighbours spoke their own?

By 1990, this narrative had crystallized into target lists. Kashmiri militants specifically hunted down Pandit teachers, professors, and intellectuals. The very people who had preserved Kashmir’s literary and cultural heritage became symbols of what needed to be purged.

The Roti’s Long Shadow

From 1932 to 1990, the arc is clear. The roti that Pandits carried as a symbol of their desire to earn an honest living became, in the twisted alchemy of history, a symbol of their “privilege” and “separateness.”

The bread that they held up to say “We belong here” was interpreted as evidence that they didn’t belong at all. The peaceful protest that they hoped would secure their future became the first step toward their exile.

When History Becomes Prophecy

Today, when we look back at the Roti Agitation, we’re not just examining a historical event—we’re seeing the blueprint for how democracies can eliminate inconvenient minorities without appearing to do so.

You don’t need concentration camps or mass executions. You just need to craft the right narrative, pass the right laws, and let social pressure do the rest. You let neighbours turn against neighbours, communities turn against communities, until the targeted minority concludes that leaving is their only option.

The genius of this approach is its deniability. No one ordered the Pandits to leave Kashmir in 1990. They simply found themselves in a place where their children couldn’t go to school, where their temples were being destroyed, where their names appeared on hit lists, where the very air they breathed had become toxic with threat.

So, they left. And then they were blamed for leaving, for “abandoning” Kashmir, for “choosing” exile over resistance.

The Truth That Died With the Truth-Tellers

“Main Kashmir hua, is liye bhi katl bar bar hua” (मैं कश्मीर हुआ, इस लिए भी क़त्ल बार बार हुआ) – I am but Kashmir, and hence my truth was slaughtered time and again.

— Dr. Ashish Kaul

These words capture something essential about what happened in Kashmir: it wasn’t just people who were killed or displaced, it was truth itself that became a casualty.

In the end, the Roti Agitation teaches us something uncomfortable about the nature of justice, history, and belonging. It shows us how quickly the oppressed can become the oppressor, how easily yesterday’s victims can become tomorrow’s villains, how effortlessly inclusive laws can become tools of exclusion.

Most disturbingly, it shows us how a community’s greatest virtues, their commitment to education, their belief in inclusive governance, their faith in the possibility of coexistence, can be turned into the very weapons used to destroy them.

The rotis that Kashmiri Pandits carried in 1932 were more than symbols of livelihood. they were symbols of hope that reason could prevail over prejudice, that merit could triumph over demographics, that a small community could find security through service rather than separation.

That hope died slowly, over decades, in the space between the roti raised in protest and the suitcase packed in exile. And with it died something essential about what Kashmir could have been, not just for Pandits, but for everyone who called that valley home.

The roti became a sword. The bread became a weapon. And the valley of Kashmir learned, once again, that in the arithmetic of identity politics, truth is always the first casualty, and rarely the last.

It is well researched and facts showcase the resilience of this minority community and the dangers posed by the majority community in Kashmir who despite having Sanatan roots and traditions which are still relevant in their lives are influenced by the fanatic state of their religion which is hell bent in destroying the mankind as is evident from their actions across the globe.Time for the majority community to understand the ethos of the land of their ancestors which has been the cradle of Civilization where they have given so much to world which modern science is still trying to understand.Kashmir is land of Sharda ,land of Knowledge where clouds of Ignorance have engulfed which needs to be vanish so that it gives humans and humanity a direction to live and live for purpose and live with dignity for this planet earth and for values which are possible and recognised from this land only.