Unsung War of Prince Saloon and Mohd. Subhan Hajam Against Kashmir’s State Regulated Prostitution

When Srinagar police arrested five people in a prostitution bust on August 23, 2023, the hushed conversations revealed more than contemporary discomfort. They exposed a collective amnesia about Kashmir’s darkest chapter. For centuries, organized prostitution wasn’t hidden in society’s shadows; it was the backbone of the state economy, contributing nearly 25% of government revenue through the systematic exploitation of 18,715 registered women.

Today, Kashmir conjures images of pristine Dal Lake, golden chinars, and snow-capped peaks. Yet this romanticized identity carefully erases a brutal truth: Kashmir once operated the subcontinent’s most systematically organized flesh market, where human bodies were taxed, classified, and commodified as state property.

The Sacred Made Profane

The tragedy begins with linguistic destruction. “Hafiza”, originally a term of profound Islamic respect for the learned woman, became Kashmir’s official designation for state-registered prostitutes. These women initially were skilled classical performers who “started as dancers and were given a respectable name of ‘Hafiza,'” as historians Showkat Rasheid Wani and Khawar Khan Achakzai document. But crushing state taxation forced them to “lean towards selling their bodies and were relegated by the word ‘gaani’ (prostitutes).”

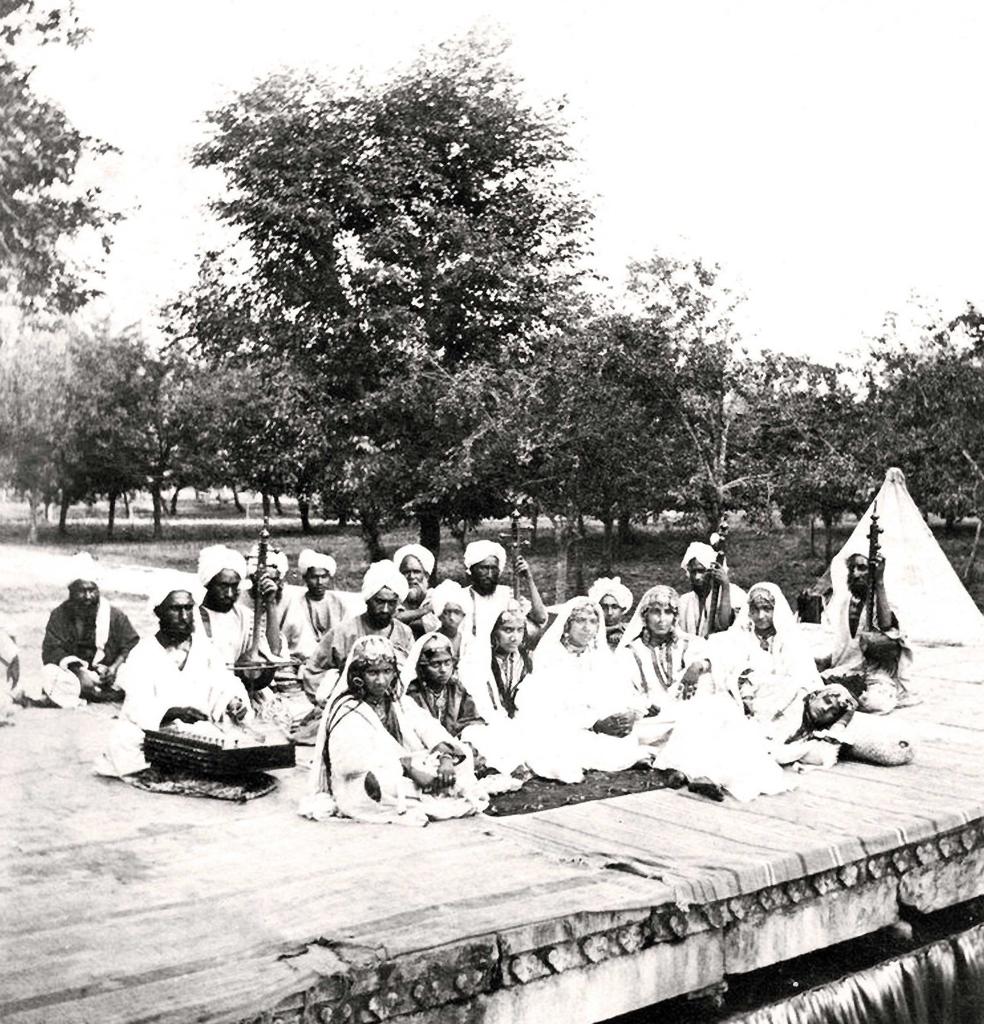

This semantic shift from sacred to profane tells the story of an entire culture’s moral collapse. Victorian photographers Samuel Bourne and John Burke captured these women in their original dignity,accomplished artists surrounded by traditional instruments, performing at venues like Shalimar Bagh for royal courts. Yet within decades, economic coercion transformed respected cultural preservers into exploited commodities.

The Mughal Pleasure Garden

Kashmir’s institutionalized flesh trade wasn’t colonial innovation it was woven into the valley’s ancient fabric.

When Mughals designated Kashmir as “Bagh-i-Khas” the special garden, they meant it literally. French physician François Bernier observed that “nearly every individual admitted to the Mughal court selected wives and concubines from Kashmir, so that their children may be fairer than the Indians and pass for genuine Mongols.” This period transformed areas like Tashwan into organized red-light districts, with the very name possibly deriving from “Tashi Bohur, a pimp who ran a brothel disguised as a herbal shop,” according to historian Akhtar Mohi-ud-Din.

The Afghan Horror

The Afghan era (1752-1819) introduced wholesale brutality. Governor Abdullah Khan, “suffering from a kidney ailment, was advised to engage in sexual relations with virgins as a remedy.” The solution? Systematic procurement of virgin daughters from wealthy families for one-night “marriages”500 rupees and a bridal gown for each girl, followed by immediate divorce the next morning. Meanwhile, “destitute Kashmiris were coerced into enslavement and transported to Kabul” as human trafficking became an export industry.

The Sikh period introduced bureaucratic innovation: systematic taxation of human suffering. This marked “the first instance when prostitution was officially recognized and subjected to taxation,” with the government collecting fifteen hundred rupees in 1836-1837. Children as young as eight became commodities, “packaged and sent off to Punjab,” with parents receiving “twenty to three hundred rupees for their children.”

The Dogra Revenue Machine

The Dogra period (1846-1947) perfected systematic exploitation into a sophisticated revenue machine. British investigator Arthur Brinkman’s damning 1867 report “The Wrongs of Kashmir” exposed how “the sale of young Muslim girls was protected and encouraged by the Maharaja, as it was highly beneficial to the exchequer.”

The scale was staggering: 18,715 state-regulated prostitutes generating 15-25% of total state revenue. Women were classified like inventory, first-class, second-class, third-class: taxed at 40, 20, and 10 rupees annually. The 1921 “Public Prostitutes Registration Rules” legalized the system, defining public prostitutes as women who “earn their livelihood by offering their person to lewdness for hire.”

The Hafizas faced deliberate economic traps designed to prevent escape. They paid “a hefty registration fee of 200 chilkee rupees per year plus half of their total earnings”, amounts calculated to ensure perpetual bondage. These women “were not allowed to marry or seek alternative means of livelihood.” When they attempted escape, they were dragged back. Historical records document heartbreaking instances where women “pleaded with officers to be allowed to marry and lead a settled life, but their requests were denied.”

The health consequences were catastrophic. Despite generating massive revenue, “no funds were allocated for their healthcare.” Between 1877-1879, nearly 20% of all patients treated at Srinagar’s mission hospital suffered from venereal diseases, a direct consequence of state-sanctioned exploitation.

The Barber’s Crusade

In this landscape of institutional cruelty, change came from Mohammad Subhan Hajam, a humble barber who owned the Prince Hair Cutting Salon near Lal Chowk. Living in the red-light district, Subhan was tormented not by the songs or fighting, but by “the cries of anguish from the unfortunates recently forced into a cruel life, many quite young, who had been sold under the preteens that marriages had been arranged,” as educationist Tyndale Biscoe documented.

Subhan’s methods were dangerously simple: he wrote pamphlets exposing the trade, preached in streets, and physically positioned himself outside brothels to prevent customers from entering. He composed poems in Kashmiri and Urdu, creating “Hidiyat-Nama” (guidelines) exhorting people to stay away.

The backlash was brutal. The influential district chief “Khazir gaan” orchestrated attacks through pimps and corrupted police. Multiple false cases were filed against Subhan. But his moral authority transcended religious boundaries, winning support from “Muslims, Pandits and Sikhs alike.”

The breakthrough came when Molvi Mohammad Abdullah Vakil raised the issue in the Praja Sabha in 1934. Under mounting pressure, the State Assembly passed “The Suppression of Immoral Trafficking Act.” Police officers were dispatched to red-light areas across northern India, with officer Abdul Karim successfully repatriating “a large number of unfortunate girls.”

The Great Erasure

The rehabilitation was remarkable yet unacknowledged. Former Hafizas “took to handlooms while others were absorbed in silk factories”, one of history’s most significant transitions from exploitation to dignified work.

Today’s Kashmir identity is built around natural beauty and cultural sophistication, authentic aspects that deliberately bury uncomfortable truths. The thousands of women who suffered under state-sanctioned exploitation have been written out of history.

This isn’t mere historical curiosity. It’s a warning about how economic necessities justify profound moral compromises and how societies forget uncomfortable truths. When police bust prostitution rackets today, it feels like aberration rather than echo of the valley’s most systematic exploitation.

Mohammad Subhan Hajam’s victory reminds us that sometimes the most powerful force against institutional evil isn’t grand political movements, but one person with moral clarity refusing to accept “this is just how things are.” In forgetting the Hafizas, we risk forgetting the vigilance required to prevent such horrors from returning.

Intrigued, superb penning, very engaging