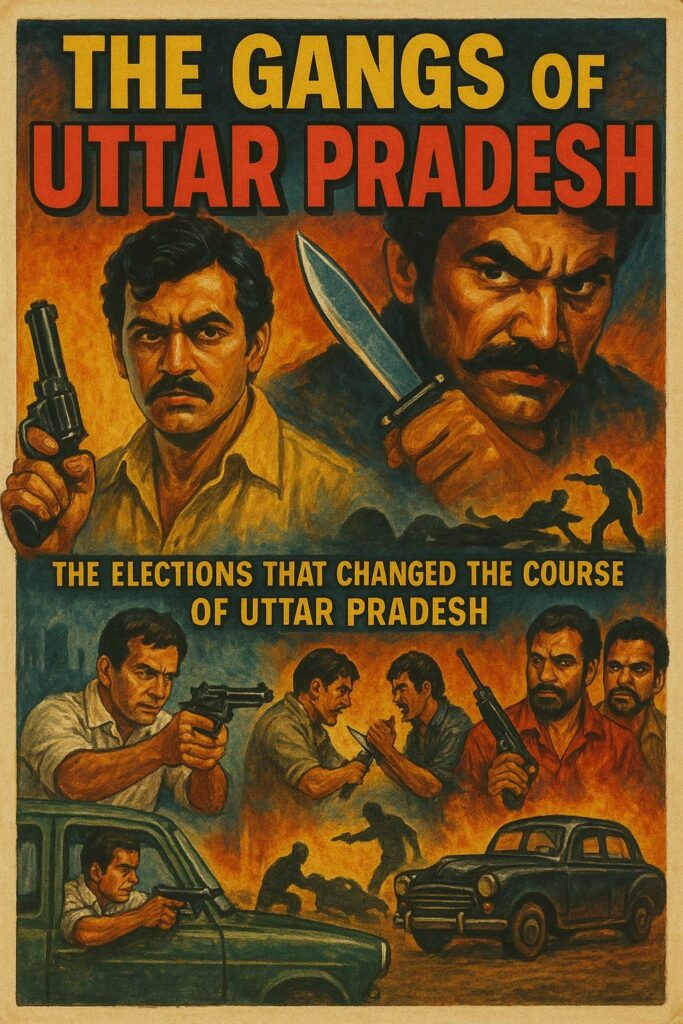

In 1981, a gangster didn’t just win an election, the victory unleashed four decades of blood, bullets, and billions that transformed India’s largest state into a criminal empire. The real Mirzapur story is far more terrifying than any web series dared to show.

From the gritty lanes of Mirzapur’s gun factories to the blood-soaked constituencies of Purvanchal, popular culture has turned Uttar Pradesh’s gangster-politician saga into cinematic gold. Web series like “Mirzapur,” “Arya,” and “Scam 1992” have captivated audiences with tales of power, betrayal, and violence that seem too outrageous for reality. Bollywood’s “Gangs of Wasseypur” immortalized the coal mafia’s brutality, while “Apharan” explored the nexus between crime and politics. These aren’t mere entertainment, they’re windows into a world where democracy itself became hostage to criminal ambition.

Yet behind the dramatic license of these productions lies a chilling truth: the real story of how Uttar Pradesh transformed from India’s political heartland into its criminal capital is far more sinister than any screenplay. The genesis of this transformation can be traced to a single, audacious moment in 1981 when the underworld didn’t just influence an election, it won one.

In the labyrinthine saga of Uttar Pradesh’s political evolution, the 1981 Nautanwa election in Maharajganj district stands as a watershed, an audacious moment when the underworld stormed the bastions of democracy. When Amarmani Tripathi, a shadowy strongman, vanquished the incumbent Congress-I MLA Virendra Pratap Sahi as an Independent candidate, it was no mere electoral upset. It was a clarion call, heralding the formal consecration of criminal politics in UP.

The Birth of India’s Chicago (1970s-1980s)

By the late 1970s, eastern Uttar Pradesh had become a crucible of feudal violence, illicit commerce, and a burgeoning nexus between criminals, police, and politicians. The districts of Gorakhpur, Deoria, Azamgarh, and Maharajganj earned the moniker “India’s Chicago” from a sensationalist press, evoking the gangland chaos of Prohibition-era America.

The criminal syndicates thrived on three nefarious enterprises: land grabbing through corrupt records and brute force, government contract monopolies secured through intimidation and bribery, and illegal mining coupled with cross-border smuggling via the porous Nepal border. Gangsters like Hari Shankar Tiwari emerged as enforcers, while Tripathi himself plundered agricultural estates, amassing wealth through coercion.

This lawless ecosystem was sustained by a corrupt nexus where local police avoided confronting politically connected gangsters, judicial processes were stymied by intimidated judges, and politicians enlisted criminal networks for election rigging. The 1981 Nautanwa election became the template: Tripathi’s victory rested on booth capturing, voter intimidation, and financial muscle, a deluge of liquor, cash, and contract promises that swayed the electorate.

The Deadly Reign of The Mafia Raj (1990s-2000s)

The 1990s witnessed the apex of criminal-political fusion. Hari Shankar Tiwari ascended to ministerial portfolios, manipulating tenders and police postings with impunity. Mukhtar Ansari, a five-time MLA from Mau, built an empire on contract killings, extortion, and railway contracts. Even while incarcerated, he wielded influence over elections and local administration, his criminal dossier boasting over 60 cases ranging from murder to extortion.

Atiq Ahmed epitomized this transformation, transitioning from kidnapping kingpin to Member of Parliament. His reign was marked by over 100 criminal cases, yet he leveraged political clout to secure legitimacy. Ahmed’s empire, built on real estate and contract rackets, thrived on a network of loyal enforcers who terrorized opponents. These figures weren’t outliers—they were the new normal, embodying the seamless fusion of crime and power that Tripathi’s 1981 victory had pioneered.

The early 2000s brought both criminal dominance and its partial containment. Tripathi’s 2003 downfall, following his conviction in the Madhumita Shukla murder case, a poet killed for exposing his affair, marked rare accountability. Under Mayawati and Akhilesh Yadav, police encounters (2007-2012) eliminated several gangsters, yet many adapted, pivoting to “legitimate” ventures like real estate.

The Reckoning and What Remains (2020s)

In the last few years, much has changed, the law of the land has visibly improved under stricter administrative measures, targeted encounters have dismantled criminal networks, and asset seizures have crippled mafia operations. The deaths of Mukhtar Ansari in 2024 (judicial custody) and Atiq Ahmed in 2023 (controversial encounter) signalled a decisive crackdown on high-profile gangster-politicians. Yet still, there is a lot left unchanged.

The spectre of criminality persists in subtler forms. Over 40% of UP’s MLAs continue to have registered criminal cases, per Association for Democratic Reforms data. The system, while less anarchic than the Mirzapur of popular imagination, remains far from cleansed. Politicians with criminal backgrounds have simply learned to cloak their influence in the veneer of legitimacy, operating through proxies and legitimate businesses.

The 1981 Nautanwa election was not the genesis of criminality in Uttar Pradesh, but it was the moment it was legitimized as a political strategy. Amarmani Tripathi’s victory illuminated a grim truth that no web series has fully captured: winning elections offered gangsters not just power, but a shield against justice. While the brazen violence of the 1980s has subsided, the nexus of crime and power remains entrenched, embedded in systemic corruption.

Can Uttar Pradesh break free from this cycle? Only if voters reject criminal candidates and institutions dismantle their protective scaffolding. The legacies of Tripathi, Ansari, and Ahmed serve as stark reminders that democracy, when infiltrated by criminality, becomes a hostage to its own past. There are questions; has enough been done to remove crime from the social system ? Yes, a lot is being done; can the efforts be enough ? Can the damage caused to UP be undone in a fleeting manner ? Questions will remain, none the less, the battle for UP’s soul continues, and unlike the neat conclusions of streaming series, this story has no predetermined ending.