When a 17th-century merchant’s meticulous eye captured everything except what mattered most

In 1628, when Cornish merchant Peter Mundy stepped onto Surat’s docks, he brought two invaluable tools for documenting Mughal India: a trader’s forensic precision and a Protestant European’s unshakeable cultural blindness. The resulting six-year chronicle constitutes one of early modern history’s richest paradoxes,an eyewitness account simultaneously indispensable and fundamentally unreliable, capturing India’s texture while systematically misreading its meaning. Mundy’s travels through Shah Jahan’s empire reveal less about 17th-century India than about the epistemology of observation itself: what we see depends not on what exists, but on what our conceptual frameworks permit us to recognize.

Death and Spectacle: The Paradoxes Mundy Could See

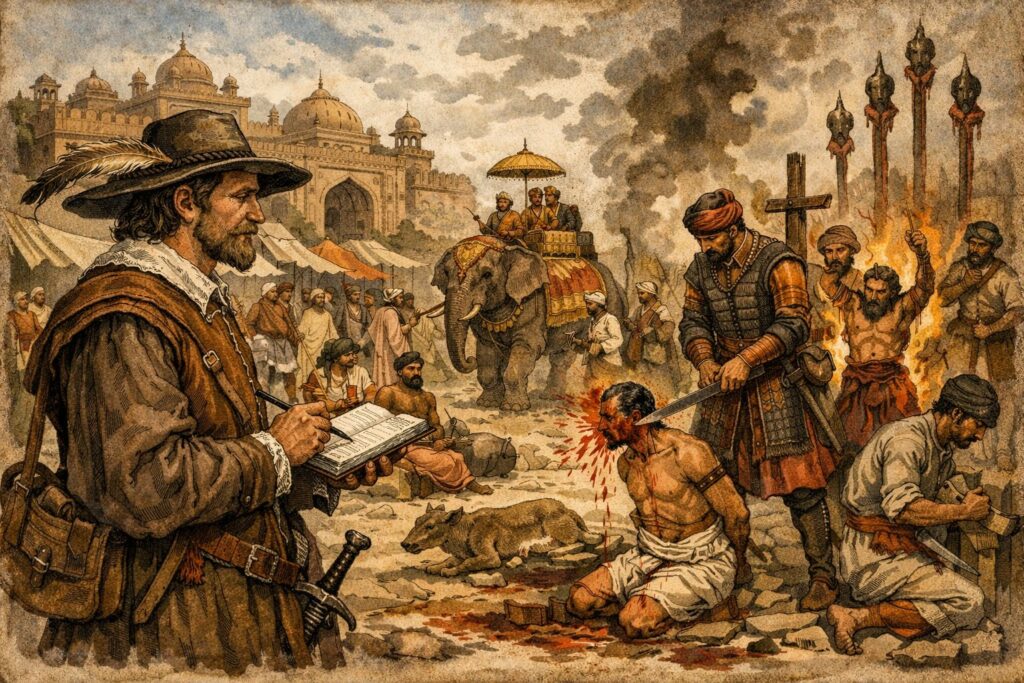

Mundy possessed genius for documenting contradiction. Between 1630-1632, he traversed territories experiencing simultaneous architectural zenith and demographic apocalypse. The Gujarat-Deccan famine claimed an estimated three to seven million lives through drought, locust plagues, and administratively diverted grain supplies. Mundy chronicled corpse-lined roads, skeletal refugee columns, wheat prices inflating 1,500 percent, and villages reverting to wilderness with merchant-like precision. He noted the catastrophe’s commercial implications silent calico looms, disrupted cargo routes with the same methodical attention he devoted to Shah Jahan’s 1632 royal procession.

That procession emerges in Mundy’s account as political theatre of extraordinary sophistication: thousands of gilded elephants, damascened war-horses, mobile pavilions functioning as portable palaces, the emperor’s passage preceded by carpet-laying and incense clouds. Mundy understood this spectacle as statecraft power performed for merchants, governors, and famine-devastated populations simultaneously. He documented skull minars (towers constructed from criminals’ heads) with visceral disgust yet strategic comprehension, recognizing them as Timurid-inherited deterrence mechanisms deployed during social unrest.

What makes Mundy valuable is his unsentimental eye for empire’s operational reality: a state capable of transcontinental logistics yet corrupted by predatory officials, magnificent in ceremonial display yet merciless in judicial violence, organized around rational revenue systems undermined by the very bureaucrats administering them. His India defied both Orientalist romance and missionary condemnation it was a working civilization, prosperous yet precarious.

Engineering and Spirit: The Sophistication Mundy Couldn’t See

Yet Mundy’s observational genius contained systematic blind spots shaped by Protestant European supremacism. His treatment of Mughal gardens exemplifies this cognitive failure. He marvelled at char bagh (four-part) gardens’ geometric water channels, cascading fountains, and underground piping systems, uncritically attributing them to “Persian hydraulic aesthetics.” What he never investigated: whether these represented Persian innovation or synthesis with indigenous Indian water engineering predating Persian influence by millennia.

Mundy traversed territories containing Harappan-era drainage systems (2600-1900 BCE), Vedic irrigation networks, Mauryan-era artificial lakes, and architecturally extraordinary stepwells (baolis) demonstrating sophisticated understanding of water table dynamics. He walked past hydraulic infrastructure representing some of humanity’s most advanced pre-modern engineering, dismissed it as unremarkable “native” construction, then credited Mughal (Islamic) gardens incorporating these very technologies while clothing them in Persian vocabulary. His blindness reveals how cultural prejudice shapes perception: sophisticated engineering remained invisible precisely when produced by “heathen” civilization.

Similarly, Mundy systematically dismissed Hindu and Muslim devotional practices as “superstitions”Diwali’s spiritual significance of light triumphing darkness, Holi’s celebration of divine play, Benares temple puja embodying sophisticated theological concepts of murti (sacred embodiment), Ganges ablutions expressing sacred geography. His mechanical descriptions inadvertently created an ethnographic archive modern scholars reinterpret beyond his biases, but his dismissals reveal 17th-century European provincialism confronting philosophical traditions that had produced the Upanishads, Bhagavad Gita, and mathematical innovations while Europe remained pre-Enlightenment.

Narratives of Power: The Questions Mundy Never Asked

Most revealing are Mundy’s silences. His account of sati (widow immolation) relies entirely on hearsay he never witnessed the practice. Yet he confidently reported Shah Jahan “curtailed” it, presenting Mughal rulers as enlightened reformers saving Hindu women from barbaric customs. This narrative conveniently obscured uncomfortable realities: the practice’s disputed actual prevalence, Mughal policies creating conditions of female economic destitution and social vulnerability, documented sexual violence against Hindu women during military campaigns, and forced conversions making self-immolation appear rational to desperate women facing violation.

By praising Mughal “prohibition” while permitting “voluntary” cases, accounts like Mundy’s whitewashed state complicity in creating the desperation driving such acts. Similarly, Mundy accepted imperial designations of armed resisters as “criminals” without questioning whether these were dispossessed peasants, tribal communities defending territories, or rebels resisting extractive taxation. His uncritical adoption of power’s narratives reveals how observers serve dominant frameworks even when documenting suffering.

Reading Against the Archive

Mundy’s testimony matters precisely because it’s flawed. His transparent prejudices allow historians to read against his interpretations, extracting empirical observations while rejecting cultural judgments. The hydraulic systems he admired without understanding, spiritual traditions he dismissed without comprehending, indigenous resisters he accepted as criminals, women’s desperation he attributed to “Hindu custom” without examining Mughal complicity,all reveal that Mundy’s greatest value lies not in what he saw, but in what his selective vision teaches about observation’s politics itself.

Every archive reflects power’s perspective. Learning to recognize what privileged observers couldn’t see or refused to see remains essential for reconstructing histories from below. Peter Mundy bequeathed not objective India but a map of 17th-century European epistemology’s limits. That legacy, properly read, proves more valuable than any neutral account could be.