In 72 hours, Nepal lost more heritage than earthquakes destroyed in decades. The Singha Durbar’s charred remains hide a darker truth: why are South Asia’s youth systematically erasing their own history?

When protesters stormed through Kathmandu’s streets in September 2025, setting ablaze the very structures that define Nepal’s identity, they did more than destroy buildings—they tore pages from the nation’s soul. The flames that consumed the Singha Durbar complex didn’t just burn wood and stone; they incinerated 117 years of institutional memory, craftsmanship, and the delicate thread that connects a nation to its past.

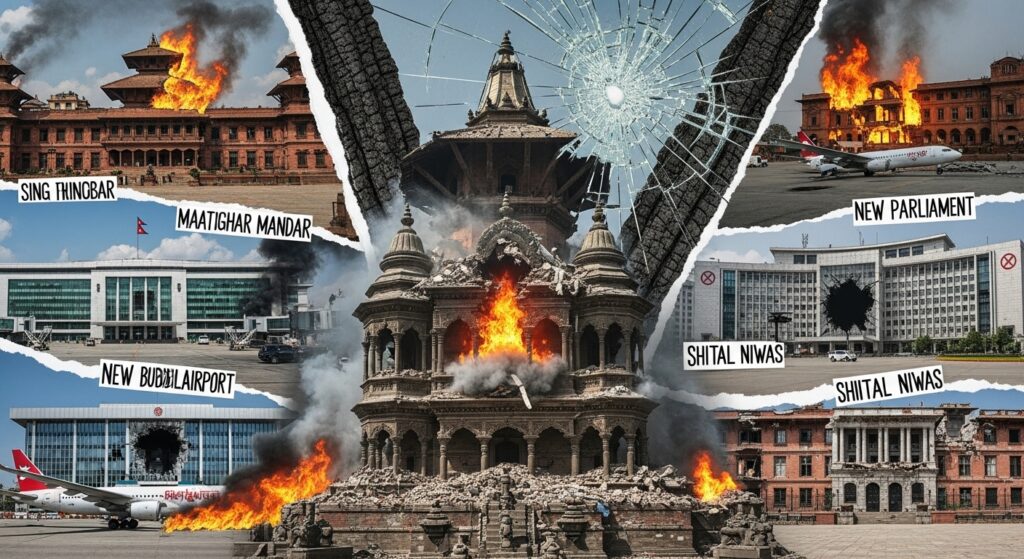

The attack on heritage monuments during political upheaval represents something far more sinister than mere vandalism. It is an assault on the collective consciousness of a nation, a deliberate erasure of the stories embedded in carved beams, weathered stones, and hallowed halls. When the Singha Durbar Palace Complex erupted in flames, Nepal didn’t just lose a building—it lost a piece of its architectural DNA. Here is the list of cultural casualties:

The Singha Durbar: Where Lions Once Roared

The Singha Durbar, conceived in June 1908 by Prime Minister Chandra Shumsher and crafted by architects Kumar Narsingh Rana and Kishor Narsingh Rana, stood as a testament to Nepal’s unique architectural fusion. This wasn’t merely a government building; it was a neoclassical and neo-Palladian masterpiece that married European grandeur with Nepali sensibility. The palace represented a moment in history when Nepal dared to dream beyond its borders while remaining rooted in its cultural soil.

The irony cuts deep,the very structure that housed both chambers of Nepal’s Parliament became the target of democratic rage. When protesters broke into the parliament building and set it on fire, they attacked the physical manifestation of the democratic ideals they claimed to defend. The flames that licked at century-old timber didn’t discriminate between political allegiances; they consumed the meeting rooms where countless debates shaped modern Nepal, the corridors where historic decisions were made, and the chambers where the voice of the people found expression.

The New Parliament House: Democracy’s Wounded Symbol

The destruction extended beyond the historic Singha Durbar to encompass the new parliamentary infrastructure,buildings that represented Nepal’s contemporary democratic aspirations. These structures, while lacking the historical gravitas of their older counterparts, embodied the nation’s commitment to modern governance and institutional development. Their destruction sends a chilling message: that in moments of political fury, even the newest symbols of democracy are not sacred.

Infrastructure as Identity: The Airport’s Ashes

The violence at Gautam Buddha International Airport, where protesters torched government vehicles and vandalized property, represents an attack on Nepal’s aspirations for global connectivity. This modern infrastructure, named after the enlightened one who preached peace, became a battlefield where enlightenment gave way to destruction. The airport symbolized Nepal’s desire to open its doors to the world; its vandalization closed those very doors with smoke and ash.

Maitighar Mandala: The Heart Under Siege

The protests centered around Maitighar Mandala, one of the city’s most iconic landmarks, transformed this symbol of urban planning into ground zero of cultural destruction. Built during the Panchayat era as a testament to modern Nepal’s organizational capabilities, the monument found itself surrounded by the very chaos it was designed to prevent. The mandala—a symbol of cosmic order and harmony—witnessed its antithesis as order dissolved into mayhem.

The Personal Made Political: When Homes Become Targets

The systematic targeting of political residences—the homes of Sher Bahadur Deuba, President Ram Chandra Poudel, Home Minister Ramesh Lekhak, and former PM Pushpa Kamal Dahal—transformed private spaces into political battlegrounds. The vandalization of Communist Party of Nepal (UML) and Nepali Congress headquarters completed this pattern of personalized political destruction.

Most tragically, this wave of violence claimed a human life, the demise of an ex-Prime Minister’s wife, a casualty that transforms statistical destruction into personal grief. Her death serves as a stark reminder that when cultural monuments burn, human lives hang in the balance, and the cost of political rage extends far beyond broken stones and charred timber.

The Impossibility of True Restoration

Herein lies the cruellest truth: while governments may rebuild, restore, and reconstruct, the authentic spirit of these structures can never be recovered. The Singha Durbar may rise again from its ashes, but it will be a facsimile, a well-meaning but ultimately hollow reproduction of what once was. The craftsmen who laid each stone with reverence, who carved each beam with ancestral knowledge, who understood the sacred geometry of space and meaning, they are gone, their techniques buried with them.

Modern restoration, no matter how meticulous, carries the clinical precision of contemporary methods rather than the spiritual devotion of traditional craftsmanship. The new structures may look identical, but they lack the soul that only time, tradition, and authentic creation can provide. They become monuments to loss disguised as symbols of recovery.

Every crack that appears in hastily repaired walls will serve as a permanent scar on the nation’s Memoria reminder of the day when political passion overwhelmed cultural preservation. These scars will tell stories to future generations: stories of a time when a nation’s children turned against their own inheritance, when the guardians of democracy became its destroyers.

A Regional Malady: The South Asian Pattern of Cultural Destruction

Nepal’s tragedy is not an isolated incident but part of a disturbing regional pattern that has plagued the Indian subcontinent. From the systematic destruction of cultural sites in Pakistan during communal violence to the vandalization of historical structures during riots in India, the region has witnessed a troubling normalization of heritage destruction as a form of political expression.

Bangladesh has seen similar losses to its archaeological treasures during periods of political upheaval, while Sri Lanka’s civil conflict left countless cultural monuments damaged or destroyed. This pattern suggests a deeper malaise,a disconnect between contemporary political movements and the cultural heritage that defines these nations’ identities.

The reasons are complex and interconnected: rapid urbanization that devalues traditional architecture, political instability that prioritizes immediate concerns over long-term cultural preservation, and perhaps most troublingly, a growing generational gap where young people see these monuments not as shared heritage but as symbols of oppressive systems to be overthrown.

The Eternal Crack in Time

As Nepal surveys the damage and begins the painful process of counting its losses, the nation must grapple with a fundamental question: How does a society heal when its own children have wounded its cultural soul? The answer lies not in the speed of reconstruction but in the depth of reflection that follows.

The flames that consumed Nepal’s heritage have revealed something profound about the relationship between political expression and cultural preservation. They have shown that in moments of extreme passion, the line between justified resistance and cultural vandalism becomes perilously thin. They have demonstrated that the price of political upheaval is often paid not just by the living but by the memory of the dead: the generations of craftsmen, architects, and visionaries whose work now lies in ruins.

Nepal’s heritage sites will be rebuilt, its government buildings will be reconstructed, and life will continue. But the scars will remain,not just on the restored facades but in the collective memory of a nation that watched its children burn down the house that sheltered its dreams. These scars serve as both warning and wisdom: that the true strength of a democracy lies not in its ability to destroy the symbols of power but in its capacity to preserve the cultural heritage that gives that power meaning.

The cracks in Nepal’s monuments will heal with time and care, but the crack in the nation’s cultural confidence may prove far more difficult to repair. For in those moments when flames consumed history, Nepal learned a bitter truth: that the distance between construction and destruction, between heritage and ash, between memory and oblivion, is no greater than the length of a matchstick and the depth of political rage.